AI allows more time for students, North Dakota educators say

BISMARCK, N.D. (North Dakota Monitor) — When Connor Fitzgerald sits down to create a lesson plan for his high school English class, he goes about it a little differently than he used to. Instead of spending hours on research and coming up with ideas, he punches words into a textbox on his computer and waits just a few seconds for results.

This new way of approaching lesson planning — one not using textbooks but algorithms — is just the tip of the iceberg of how artificial intelligence is revolutionizing the classroom. Teachers also use it for preparing quizzes, generating presentations, keeping track of student progress, and seeing how students might be challenged.

For Fitzgerald, the benefit of using AI for class preparation is saving time so he can instead focus on more critical tasks such as student engagement.

“That’s ultimately the goal, at least on the educational side of it,” he said. “How do you use this new tool, not to replace you but to ease your workload to do other things?”

Fitzgerald, an English teacher at Milnor Public Schools, has been on the front lines for almost a year about how best to use AI in his classroom. He attended state training on its uses last fall and is helping to write his school’s AI policy, based on state guidance. Teachers can use AI for such things as lesson planning and prep work, for instance, and students can use it for idea generation.

Educators and AI

Fitzgerald said he’s received training on the ethical use of AI and how AI can help educators regain some of their time.

“The idea with the training was that AI is brand new technology, and so how do you use it in the classroom in a way that is ethical and works best for you,” he said. “I use a lot of AI tech since that training for creating grammar worksheets — essentially, taking what we already do as teachers and shortening the worktime so I don’t have to sit there and come up with 45 example sentences to put in a worksheet when I can have the computer create it for me.”

Fargo Public Schools uses AI in much the same way and has seen similar benefits, including saving time on repetitive tasks, according to Liann Hanson, director of standards-based instruction.

“We’re using it in practical ways that save time and support student learning,” she said.

Examples include generating rubrics, adjusting reading levels, designing assessments, and producing visuals.

“This helps teachers devote more attention to individualized instruction and relationships with students,” Hanson said.

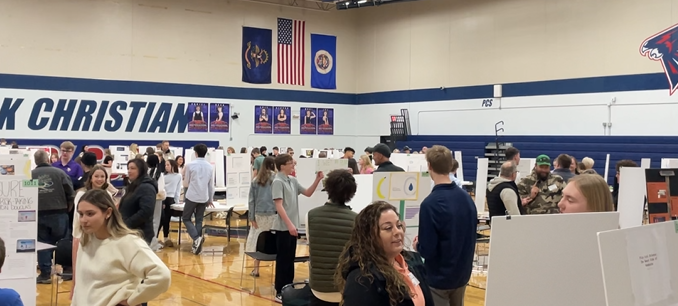

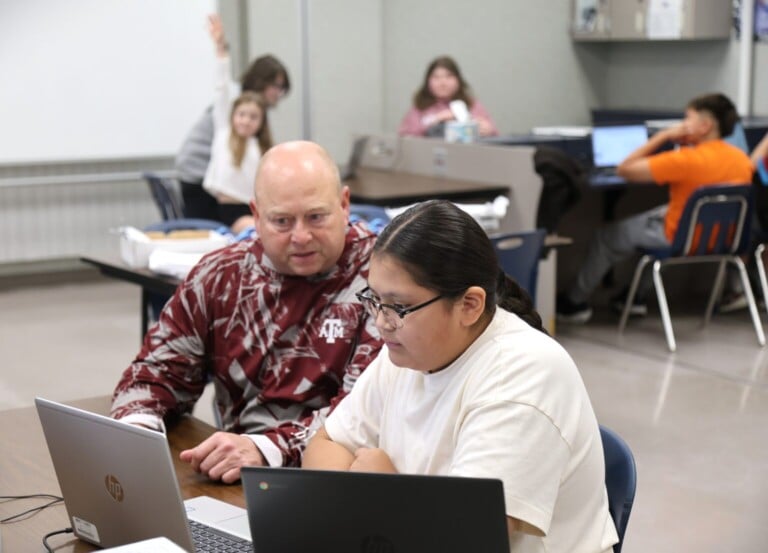

A student works on building a virtual cabin in a computer-aided design class on Oct. 8, 2025, at Horizon Middle School in Bismarck. (Photo by Andrew Weeks/For the North Dakota Monitor)

Jeff Fastnacht, superintendent for Bismarck Public Schools, said some teachers and principals have intentionally stayed away from using AI while others have jumped on board with enthusiasm. Fastnacht uses AI every day, noting it makes his job easier.

“I get more done, and I think I’m a better superintendent because of that,” he said.

Fastnacht believes the same could be true for teachers who use it.

“Teachers are drowned by the number of reports and requirements put on them, the expectations they have to execute in the classroom, the sheer number of things that distract their time from actually working with a child, which should be their primary focus — working with children,” he said.

However, he said teachers are cautioned on the limits of AI. “What a computer can’t do for you is digging into a kid and diagnosing what the learning challenges might be,” he said.

Fastnacht said much like the internet revolution of the 1990s, some educators are leery about the potential uses of AI, perhaps even worried about how far it will go in replacing the teacher. He’s not worried, however, and said it’s just another tool to use, not a replacement tool.

Hanson, from Fargo Public Schools, echoed similar sentiments: “Importantly, teachers always review and apply their professional judgment. AI is a support, not a replacement.”

Students and AI

Most North Dakota schools who are using AI allow students to use it in the classroom for simple tasks. But first they are taught the acceptable uses of it. Students and their teachers also are taught to be “good prompters,” or how to ask the technology appropriate questions to get the most out of it.

“There’s different levels of AI intervention,” Fastnacht said. “The skill of prompting, the skill of having a dialogue with AI and anticipating learning, how you want data represented back to you. That’s a whole process of learning how to prompt AI.”

At Milnor Public Schools, Fitzgerald said his approach is basic, that students can use AI for idea generation, not for class work.

“I tell them as long as they submit what they put into AI and what they got out of it, along with their assignment, then I will probably be OK with it,” he said.

For oversight, Fitzgerald said it’s so far been a “trust, guess and check” process; the check aspect for him means typing parts of a student’s work into a program to see if AI was used. “It’s basically AI checking for AI,” he said. But it’s not a perfect process and he tries to vet the work himself, often scouring several websites.

In some respects, Fitzgerald said it’s difficult to say how much AI has benefited students. Unlike him, he hasn’t noticed much reduced work time for them. “It’s a little different in that regard,” he said. “For them, it’s getting creative input on the way into an assignment.”

Ethical considerations

Educators said since AI is here to stay, it’s best that teachers and students learn how to use it appropriately. In that light, Bismarck Public Schools in September created training for educators about the different AI tools available, such as ChatGPT, Gemini and Microsoft Co-Pilot. Among the topics are using strong, specific prompts; being transparent with students; reviewing work carefully and protecting privacy; and how to harness visual element tools such as Canva. The training reinforces what the district’s “guardrails” are with regards to the technology, Fastnacht said. Protecting student information is paramount.

Fitzgerald said teachers must be careful what they put into AI programs for fear that personal information might unintentionally be regurgitated in some fashion.

The Fargo school district provides guidance and expectations because of the risks of AI, Hanson said.

“The main drawbacks of AI are the potential for bias, inaccuracies, privacy concerns, overreliance, and issues of academic integrity if students misuse tools,” she said.

Fitzgerald said although AI should be approached with caution and oversight, there are benefits of using the tool in the classroom for both teacher and student. But he expects it might have its limits.

“I don’t know how much further it will go in terms of what it’s allowed to do in the classroom now,” he said. “I can’t at this point imagine what I would do with it outside of it helping me reduce my workload.”